A Tall Warehouse Order For a National Retailer

A Tall Warehouse Order For a National Retailer

Whitesell is building the state's loftiest distribution center

By Evelyn Lee (article appeared in April 30, 2007 issue of NJBIZ.)

A South Jersey developer is constructing what it says will be New Jersey's tallest distribution center. It will allow for denser storage of goods within a smaller footprint along with other benefits, the company says.

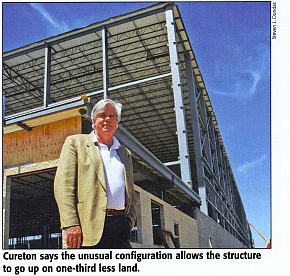

"There's twice as many goods that can be kept because the volume is twice as big as a normal building," says Richard Cureton, president of Whitesell Co., a Delran based developer that owns the Haines Center, a 900-acre industrial park on Route 130 in Florence and Burlington townships where the warehouse is being built.

At 80 feet tall, the 721,000-square-foot build-to-suit warehouse will be twice the height of most Garden State warehouses, according to Cureton. He says the warehouse will have a product storage height of 68 feet significantly more than the 30 to 36 feet found at conventional distribution sites and a 700-foot width compared with the 400 to 600-foot width of standard warehouses.

The building's overall volume comes to nearly 53 million cubic feet, double the amount available in a warehouse with the same square footage but half the height, Whitesell says.

While Cureton declined to estimate the overall cost of the project, real estate experts placed it between $70 million and $75 million, given the local land value of about $18 a buildable square foot. The warehouse could be the forerunner of other tall distribution centers, says George Molloy, senior managing director at commercial real estate brokerage Studley in Iselin. "If it's successful, you know their competitors will look upon that facility [as an example]," Molloy says. "Over the next five to 10 years, I think you'll see a lot more buildings of that height. You're going to have to build up, because land is so expensive."

But Geoff Sisko, vice president of Gross & Associates, a logistics-consulting firm in Woodbridge, doubts that the project will trigger a wave of similar facilities because of the cost of constructing and operating such a facility and its lack of adaptability to other uses. "Most people don't need that dense a storage with that fast a throughput," Sisko says, referring to the amount of goods that can be moved in out and out of the warehouse in a given period.

Many local zoning regulations will limit the number of tall distribution centers, Sisko adds. "Most zoning codes are because of visual things," he says. "In most communities, it's very difficult to get a 70- or 80 foot building built because of its visual impact."

Whitesell is constructing the facility, its first high-rise warehouse, at the request of its client, a national home goods retailer that the developer has declined to identify. Industry sources say it will be Union-based Bed, Bath & Beyond Inc.

"[The client} needs that much space in order to satisfy the 50 or so stores they're intending to serve in the mid-Atlantic area," says Cureton says. He expects construction, which began last fall, to be completed next January.

Less floor space enables Whitesell to build the warehouse on 66 acres, rather than the 100 acres that a conventional distribution center with the same storage capacity would require. The company says this will reduce the overall cost of land that will be figured into the rental rate. The company did not disclose rents for the warehouse, but said rent for the typical industrial building in the area ranges between $5.50 to $6 a square foot.

Cureton says the height of the building will allow the tenant to cut additional costs. "There's about half the floor space, so your horizontal activity is cut in half," he says. "If you're driving only the half the distance with your forklifts, then you only need half the people."

Meanwhile, automated cranes that run along floor and ceiling rails will handle the job of stocking and removing items from the warehouse racks. Cureton says a computer system will control where everything is being placed.

But automating warehouse operations, while reducing employee costs, comes at a price. "The equipment to operate a facility like this is more sophisticated, so you have some additional costs to deal with," says Cureton.

Moreover, while the warehouse will be built with the same materials used in standard storage facilities, "the structure has to be much more robust than a traditional [building}," he says.

For example, the warehouse must be able to withstand higher winds than a building lower to the ground, and the floor must be "superflat" and extra-strong to accommodate the increased weight of goods.

The fire protection system will also cost more since supplemental in-rack sprinklers are required by code when a building exceeds 45 feet in height.

"On a cost-per-square-foot basis, it's much more expensive than a traditional building to construct," Cureton says. But he calls cost-per-volume a more accurate measure because the warehouse's storage capacity is measured in cubic feet rather than square feet. "On a cost-per-volume space, it's about the same," he says. •

E-mail to elee@njbiz.com

Reprinted with permission from the April 30, 2007 issue of NJBIZ. www.njbiz.com. Copyright 2007, NJBIZ all rights reserved.

For more information about reprints from NJBIZ, contact Wright's Reprints at 877-652-5295

Current News|Archived News